21/12/2019

Leïla Slimani the Feminist (?)

One of the most emblematic figures of the latest francophone literature, Leïla Slimani gained public recognition when she received the Goncourt Prize in 2016 for Lullaby, a story about a Parisian nanny, who, as a result of mental instability, murders her two charges. It is a flashback novel, which begins with a rather crude description of the crime scene, focusing afterwards on the circumstances prior to the infanticide. This narrative solution intensifies the suspense, as readers follow the story of the relationship between the babysitter Louise and the family, without knowing, until the last pages, the exact reasons for the murder.

Yet, neither the technique nor the plot determine the value of this book, but rather the polemic that Leïla Slimani raises about the status of women in today's society. At first sight, liberated from the shackles of gender inequalities, they invariably are bound to their ancestral image, to social expectations (vis-à-vis their behaviour, appearance, aspirations) from which various feminist movements failed to completely free them. According to a wide range of readers and critics, Slimani contributes – through her writing – to combating the still dominant concept of stereotypical womanhood. One might wonder though whether their opinions are entirely justified.

Lullaby portrays two female characters, Louise and Myriam, who, at first glance, appear to be polar opposites. Different in terms of age, education, social background, they share a significant part of their existence – femininity – and what is often intrinsic to this condition: motherhood. The emancipated Myriam refuses to submit her life to the upbringing of her children, Mila and Adam, and chooses, like so many other Western women, to pursue her professional career. It is Louise who, for a rather modest remuneration, will act as mother. In Louise’s eyes, this job constitutes a financial and psychological boon, allowing her to compensate for her previously failed family life: as if looking after Mila and Adam, taking care of her employers’ home, spoiling them with her tasty dishes could erase unhappy experiences and replace them with unforgettable memories. It goes without saying that Louise is only a surrogate mother and when the children are old enough to go to school, her job must end. She hopes, for a short time, that Myriam will get pregnant one more time, which would extend her contract (thereby her role as a “mother”) and give her again – even for a few short years – a place in this new family. Alas, these hopes turn out to be in vain: it is impossible to escape from her destiny of a poor divorcee, living in the drab Parisian suburbs, whose daughter, for a long time, has not given any sign of life. This too violent change drives Louise to madness and leads her to infanticide. Slimani seems to warn her readers: you cannot atone for a failed motherhood!

The novelist is not more forgiving towards Myriam herself, who, in one way or another, is punished for her life choices: for putting professional life over motherhood. One might indeed have the impression that some occult forces liberate her from this unwanted role as a mother, from this burden which hindered her professional and personal fulfilment. Her story is therefore opposed to the maternal figure widely spread in Western popular culture, sometimes defined using the noun "supermother", a term referring to a woman who fulfils her functions as a parent, while meeting professional requirements, leading an interesting private life and caring of her figure. Paradoxically, the example of Myriam from Lullaby teaches us that reconciliation of these social requirements is impossible, and even blameworthy. Isn't the heroine implicitly punished for refusing to devote herself entirely to motherhood?

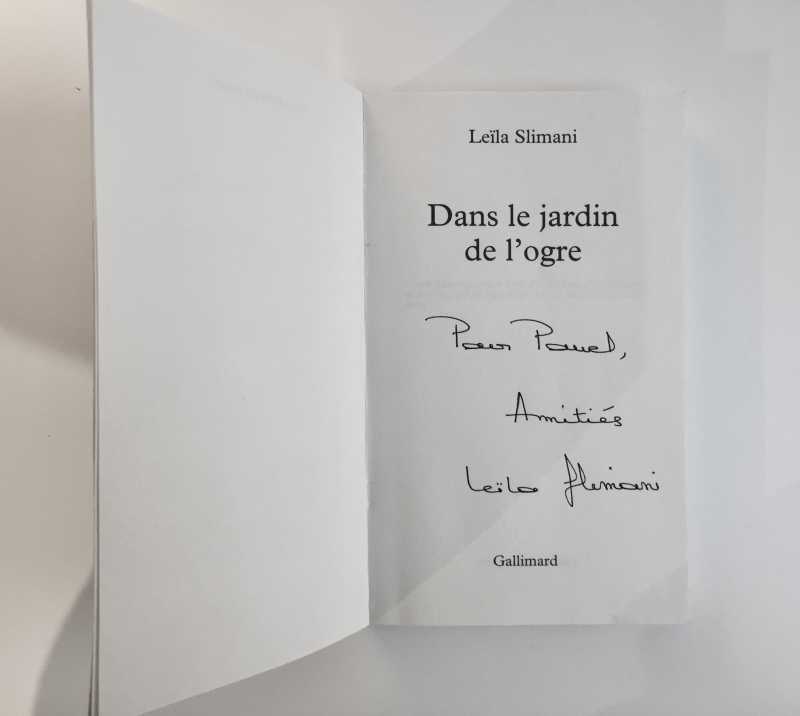

Unconsciously or deliberately, Slimani advocates the traditional concept of femininity. This message was already expressed in her first book Adèle (2014) which, as the back-cover reveals, is "a fierce and visceral novel on sexual addiction". The text tells the story of the eponymous Parisian mother and wife, whose existence is interspersed with countless extramarital relationships. It is worth noting that Slimani tries to explain her heroine's unbridled sexuality as a mental disorder. Would it be the same if Adèle was a man? Would the novelist associate this insatiable thirst for conquest with a sickly state if it were a male character? Would she classify him as a sex addict?

It seems that, contrary to popular belief, Slimani disapproves of certain female choices, that her writing, far from being feminist, contributes to widening the gap between what women can be and what society expects from them. Slimani is therefore a much less liberated author than the media and readers claim. So, what explains this misinterpretation of her fiction?

The problem lies probably in the discrepancy between what, according to all appearances, a novelist born and raised in a Muslim country must express in her books and the themes addressed by Slimani. Lullaby and Adèle deal with controversial themes such as infanticide, nymphomania, failed motherhood or motherhood as an obstacle to self-realisation. We are somewhat surprised that these texts were written by an author of Maghreb origin. Rarely discussed in her native country, these subjects earn her the label of progressive and feminist. An author defending gender equality would resent Adèle for leading an eventful sex life? Would a feminist writer refuse Myriam (Lullaby) a professional career and a rich and fulfilling existence without punishing her for her choices?