09/06/2020

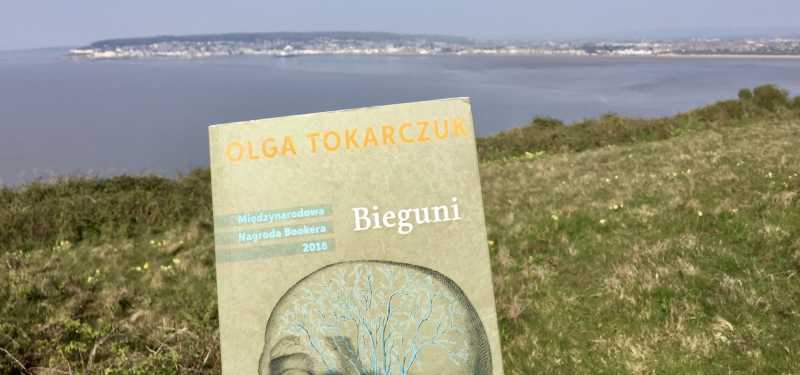

Why is Olga Tokarczuk not my favourite writer?

This article about the work of the 2018 Nobel laureate may baffle you. Firstly, I will not comply with the golden rule unofficially imposed on every Pole who dares to write about their national literature in a foreign language: "you will write flatteringly about it or not write about it at all". Furthermore, my text, being not very laudatory, will certainly recall the opinion of the ruling party’s supporters as unable to accept Olga Tokarczuk’s vision, as being too progressive and not sufficiently patriotic to their taste. Some people may wonder, who is this pathetic, uneducated and pretentious guy, who dares to question in a peremptory tone the decision of the Swedish Academy? I immediately hasten to reassure my dear readers, I would not be able to find the right words to describe how much the awarding of this most prestigious prize to a Polish author made me happy! My goal is neither to criticise novels published recently in Poland, nor to support the shameful political party, but only to express my subjective and completely questionable point of view.

Tokarczuk is undoubtedly a remarkable writer. Her meticulously refined, melodious and spellbinding sentences bear witness to a great linguistic sensitivity of which only a few contemporary prose writers can boast. This unique gift encourages us to read her books, even if they do not necessarily treat on our favourite topics. With just a few words, she outlines the diegesis: her writing immediately takes us into a world of landscapes, smells and sounds, paradoxically unknown and familiar at the same time. Tokarczuk is a magician of words!

This magic also emanates from her original stories, capable of disturbing your perception of the world. She is not another author who wants to reflect reality. Her books are not other stories aiming to be “a mirror walking along the main road”. Tokarczuk transforms the imperceptible into visible, noiseless into audible, unbelievable into plausible. She does not hesitate to "drive [her] plough through the bones of the dead" to revisit stories, centuries and universes apparently well known, but, in fact, distorted and often misunderstood (The Books of Jakob). Because “there are more things in heaven and earth, than are dreamt of in our philosophy”, Tokarczuk has the courage to doubt the indubitable, to see the world through the prism of metaphysics or nature.

Following the example of the finest writers, she is not satisfied with merely telling stories. Her novels aspire to express universal messages aimed at encouraging reflection on the sense of existence (Primeval and Other Times), popularising forgotten myths (Anna In the Catacombs) and certain unknown facts (a branch of Russian Old Believers in The Flights), or highlighting the importance of an integral part of human life, yet underestimated in today’s society - dreaming (House of Day, House of Night). Tokarczuk’s work surprises with the richness of the historical, scientific and cultural details - rarely present in fiction to such a degree - which proves the extraordinary meticulousness, creative ambitions and great intelligence of the author.

A virtuoso of content and style, Tokarczuk is, nevertheless, not my favourite writer. Her mesmerising sentences, plots full of unexpected twists and exceptional demiurgic imagination do not appeal to my literary tastes, even if I would so much like to count among her most assiduous readers. Westernised, I can’t abide the abundance of metaphysical elements so characteristic of her prose. Unable to let go of the shackles of rationalism, I flip through the pages of her novels without getting caught up in the plot, without letting myself be seduced by the diegetic world, however innovative and masterfully constructed it may be. Oneiric fragments bore me, do not add much to my life as a reader. I am not able to appreciate her originality, undoubtedly too pronounced to appeal to me. The convention of fairy tales, to which the author sometimes refers, does not entirely suit me. I turn the pages, hoping that the next ones will be more marked by realism.

The fragmentary nature of Tokarczuk's prose, characteristic of many of her novels (among others House of Day, House of Night and The Flights) tires me. I get lost in the multitude of often independent threads, sometimes having the impression that I have read a collection of loosely connected stories, rather than a coherent and well-constructed whole. This narrative solution turns out to be all the more irritating, when the novelist, out of the blue, decides to break the story to make room for a new one, almost unrelated to the previous plot. What's more, Tokarczuk does not give us a manual for her book. We do not know when a given story will reappear in the text, or even if it will continue at all. Unlike some novels (Life: A User’s Manual by Perec or Hopscotch by Cortázar), this composition seems to be completely accidental and not based on a superior logic which would justify the choice of this confusing and useless technique.

It is also difficult for me to appreciate Tokarczuk’s characters. The novelist likes to describe simple creatures who act according to behavioural codes imposed by morality, physical instincts or passions, without being influenced by these three types of mental mechanisms at the same time. They are either entirely good and honest or deeply wicked and detestable (a distinction easily noticeable in Drive your Plow over the Bones of the Dead) and, thereby, hopelessly predictable and uninteresting. It is, therefore, impossible to get rid of the feeling that they are only paper figures, having little in common with flesh and bone people.

If I reluctantly reach for Tokarczuk's prose and read her novels out of duty, it is because, although quirky and innovative, they do not suit my thematic tastes. Far from wanting to depict our time, the writer turns her back on the reality, on socio-political issues, on the existential problems typical of contemporary individuals and opts for a distant world, too foreign and artificial to strike a chord with me. Acclaimed by critics and readers around the world, her texts are, in my eyes, uninteresting, unnecessarily fanciful and at times naive.

It remains to reiterate the facts stated above. This article is an expression of personal literary tastes, in no case intended to deny the talent of Olga Tokarczuk or to diminish the importance of obtaining the Nobel Prize by this author, who undoubtedly constitutes one of the most emblematic figures of Polish contemporary literature.